(Tucson, Arizona) -– This year, 2012, marks nearly 30 years of the Phelps Dodge copper strike in Clifton-Morenci. On that fateful morning of July 1, 1983, several hundred families of copper miners in Clifton and Morenci awoke to a New World. On midnight of June 30, the contract between the 13 unions representing workers at the Morenci open-pit mine had expired, marking the beginning of the end of a way of life that for many had been largely improved with unionism in Arizona. It also marked the beginning of a process of awakening that for many continues to this day.

For those unfamiliar with this history, or too young to remember, the strike against Phelps Dodge was a three-year struggle that ended with the decertification of 13 unions in 1986. Arizona’s history is peppered by conflicts between labor and a particularly repressive mining industry. The strike of 1983 was not much different, except that it struck a near-fatal blow to U.S. unionism. The impact on the economic and social fiber of the Clifton and Morenci communities also proved particularly vicious –one from which they have yet to recover fully.

The rude awakening that I mentioned was an education for everyone. This was the era of Reaganomics, of post-Vietnam recession, of economic restructuring, and of economic incentives that sent capital overseas and to Latin America. Phelps-Dodge too, had done its homework, secretly conducting feasibility studies about what it would take to break the unions at the Morenci Mine.

Union negotiators quickly learned that this strike was quite unlike any other. Phelps Dodge, with malice aforethought, had deviated from the traditional patterned bargaining of previous years in which all of the Arizona’s mining companies collectively negotiated three-year contracts with all of their unions. In 1983, waiting until after all of the other mining companies had reached agreements with their unions, Phelps-Dodge balked. They refused to follow suit and the workers at Morenci were singled out, left stranded without a contract. With this, the death warrant on the 13 unions at Morenci was sealed.

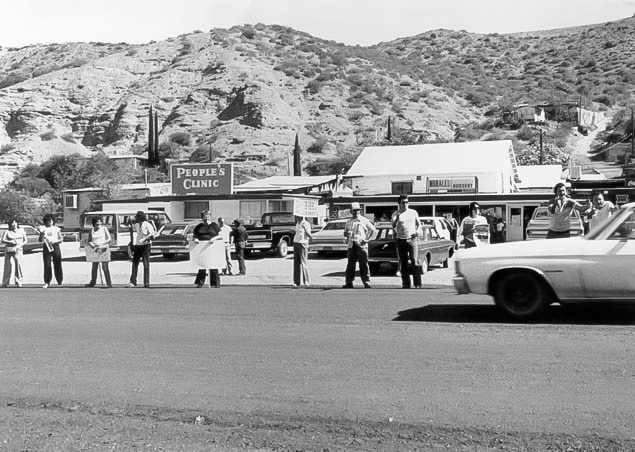

And so quickly, the communities became enlightened in the art of resistance. A Mexican physician employed by Phelps-Dodge at Morenci Hospital, Jorge O’Leary, was reprimanded by company officials for fraternizing with strikers on the picket line. On the trail of news copy, Tucson and Phoenix newspapers printed details of the stand-off and followed up with stories about how the sympathetic company doctor continued to treat striking workers and their families for free against company orders. Although continued medical benefits were guaranteed by union contract, the company had illegally denied them to strikers to pressure them to cross the picket line. For the strikers, the reprimand and ultimate firing if Dr. O’Leary served to alert the wider public about the tactics that Phelps Dodge was using. Phelps Dodge soon fired Dr. O’Leary and in this way gave the striking community a hero and martyr. It served to strengthen the community’s resolve and paved the way for the opening of People’s Clinic, a feed-store-turned-medical-office organized by the families of strikers and their supporters. The firing prolonged the course of the strike way beyond the life expectancy given by union officials, and indeed, by the company itself.

The women too, quickly became center stage. During the course of events, the women of the striking community quickly wiped the dust off of their community organizing skills. At first they came together in traditional roles that had always helped facilitate the distribution of material resources to families: food, clothing, services, or information, although this too, would change in the course of time. New roles and new perspectives forged by civil rights activism, feminism, and more normalized demands for equality and social justice had permanently changed those roles.

Mining cities awake to a strange pulsation

The communities of Clifton and Morenci were promptly tuned-in to the realities of corporatist-style decision making that takes little account of families and communities. Growing up in Clifton, and living a part of my married life in a company town normalizes a community structured by race, ethnicity, and class. Learning your place in society is reinforced by segregated neighborhoods and social distances. At the top of the structure, is the corporate hegemony—the CEOs of Phelps Dodge that guarded the bottom line. In the middle were support professionals: accountants, secretaries, and managers. Near the middle were the local union leaders with ties to officials headquartered in Pittsburgh and Washington. Unknown to us at the time, they had long given up for dead the struggle in this remote, little-known part of Arizona. At the bottom were the union locals, the rank and file, and the communities that looked to them for leadership. Also somewhere in this hierarchy, was Arizona’s governor Bruce Babbitt who, after a stand-off at the Morenci Mine gate between strikers and company officials, ordered military intervention to Clifton and Morenci to “keep the peace.” Betrayed. The governor issued this order while appearing to bring pressure to bear on the company to reach an agreement with its workers.

Thus it was that on the morning of August 19, 1983, sleepy residents of the sister cities of Clifton and Morenci awoke to a strange pulsation. At first it appeared as a muffled and distant heartbeat. It was, perhaps, for some initially confused with the steady murmur of the locomotives that routinely moved masses of ore and copper through the communities and to their destinations, until recalling that those engines had been still for weeks, since the beginning of the strike. Vietnam vets heard the low rumble, and perhaps experienced tortured flashbacks, and uneasy feelings. Those less familiar with the steady throbbing, like me, tumbled out of bed as it grew. I, like perhaps so many others, ran to the nearest window, opened curtains, opened doors, and numbly, astonishingly, and quite dumbfoundedly, attempted to make sense of what we saw.

And there it was: a miles-long convoy of armored tanks, vehicles and Huey helicopters—over 100, fully equipped with armed soldiers, swat teams, undercover agents, making its way up the mountain road, steadily, steadily, making its way to its new-front line, at the gates of the company facilities.

The drama unleashed by Arizona’s governor to quash the strike, while impressive for its day, might have been a little more familiar to us had we known a little more about Arizona’s history of mining. With a little more knowledge of our history, we would have realized that the sequence of events we were witnessing were well within the limits of the extent to which powerful companies like Phelps Dodge would do to suppress and destroy its opposition. Was it not similar to the deployment of the National Guard to the coal mines of Ludlow, Colorado, where guardsmen gunned down strikers, including women and children as they slept in their tents? Was it not similar to the use of deputized Arizona Rangers used to fire into a crowd as they marched in peaceful protest in the strike of Cananea in 1906? Was is it not similar to the use of armed vigilantes by Phelps Dodge to round up strikers and their supporters and “deport” them to New Mexico in 1917? Was it not similar to the repeated violent attacks on the wives of striking miners in New Mexico in 1950 and immortalized in the film censored during the McCarthy era, Salt of the Earth? Yet, by standing our ground, the sacrifices of those that stood fast and made a stand gave us something that no one could ever take away. It is these intangible gains that would prepare us later for the longer wars for independence and justice.

It is within this history that I’ve come to see the strikers, the women, and their supporters. In 1983 I joined a women’s organization called the Morenci Miners Women Auxiliary. Just as it had for generations, the Auxiliary emerged after husbands, brothers, fathers and sons went on strike against the notorious copper-producing Phelps Dodge Corporation. In post-Vietnam 1983, after much planning and calculation, the company refused to negotiate a contract with its 13 unions in Arizona. Just as it had for generations, the Auxiliary emerged to support their husbands, brothers, fathers and sons who went on strike. Union representatives promptly began to negotiate with the company, with the apparent “help” of their national union leaders in Pittsburgh and Washington. There was mobilization and outreach from outside the community. As the strike dragged on, the women, growing ever so impatient over evictions, food rationing, the (illegal) denial of medical care, implementation of the Taft-Hartley Act, calling out the National Guard (twice) and dwindling resources for their families, began to step outside the role of “support group.” They increasingly began to appear at rallies, got invited to speaking tours—not as bystanders and supporters, but as speakers. Months came and went—three years, in fact. As strikers left the communities, their voices not only became louder but more critical—critical of the lack of union leadership, and they began to fill the void. Thinking that the women were stepping out of bounds, many men tried to sanction them and out-right forbade them to attend organizational meetings, including union meetings, and express their concerns. (Images of Esperanza and the women of Salt of the Earth flashed back here.) Unknown to many of the rank and file, the loss of the strike had already been negotiated. We learned later, sadly, that this is how such strikes were settled: in back rooms, like pawns manipulated strategically on a checkerboard of known huelgas across our nation. Our faith was crushed to learn that somewhere, back east, people who knew nothing about us, and even so, determined our fate, ruled thumbs up/thumbs down, depending on what cards were on the table.

The roles of women in the the Great Arizona Copper Strike

So it was that the Great Arizona Copper Strike, in this sense, was business as usual. For the women of the strike, however, it was not. What was new was the idea that they could contribute to political mobilization both at local and national levels. Through web-like relational ties between individual women and their families, they found that intangible resources, such as emotional support and a sense of solidarity, was the basis for community empowerment. Their roles were key to reconceptualizing a political arena that was patriarchal, exclusionary, and hegemonic. The logic of everyday reproductive activities focused on provisioning and redistribution assumed a new importance as these became urgent, and politicized. Here, in the cradle of a political awakening, there emerged a voice that no company, no union, no government, nor man, could take away.

In the end, the strike was lost. It officially ended when strikebreakers (scabs), now Phelps-Dodge employees “voted” against unionizing in the fall of 1986. So it was that the 13 unions at the Morenci Mine were unceremoniously decertified. In many cases, more than the strike was lost. Families were disrupted and torn apart. Cousins, uncles, aunts and siblings on opposite sides of the strike were victims of irreconcilable fundamental differences. A hundred years of collective bargaining that progressively and ultimately held Phelps Dodge accountable for its economic injustices, racism, environmental degradation, and historic exploitation, were set back.

More about the on the Great Arizona Copper Strike, 1983-1986

Editor’s note: Special thanks to Dr. Christine Marin for making available the photograph of the copper strike for this essay.

© 2012 - 2024, Dr. Anna Marie Ochoa O’Leary. All rights reserved.