(Phoenix, Arizona) — Violence against women is a global problem that affects women of all ages, races, and socioeconomic backgrounds. In Guatemala, violence against women is particularly pervasive, and it often goes unpunished.

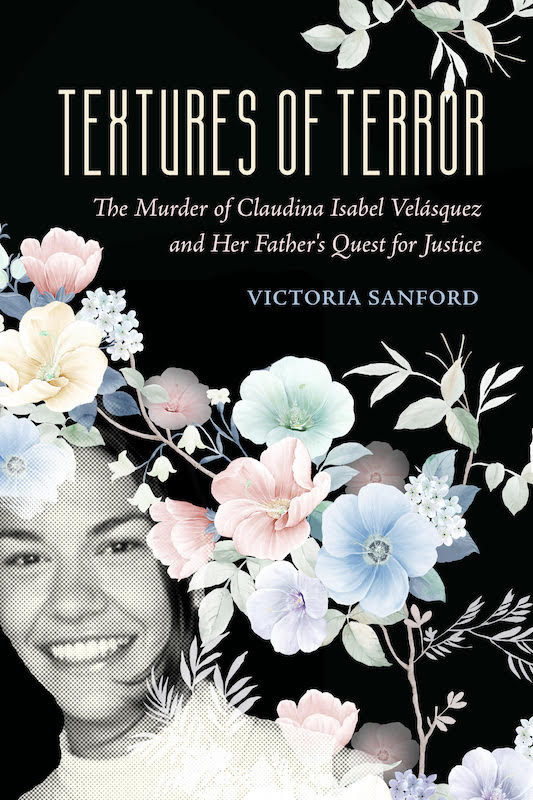

In her new book, Textures of Terror, The Murder of Claudina Isabel Velásquez and Her Father’s Quest for Justice, Professor of Anthropology Victoria Sanford explores this issue by looking into the unsolved murder of Claudina Isabel Velásquez, a law student who was brutally killed in Guatemala City in 2005.

Through a gripping first-person narrative, Sanford takes readers on a years-long search for answers alongside Claudina’s father, Jorge Velásquez, and exposes the gendered nature of power and violence in Guatemala.

Sanford also sheds light on the impact of U.S. policies in Latin America and their ripple effect on migration, demonstrating how violence against women is a driving force behind the decision of many Guatemalan women to leave their homes and seek refuge elsewhere.

Sanford’s up-close assessment of the Guatemalan criminal justice system reveals how it perpetuates inequality, patriarchy, and impunity, providing little recourse for victims of violence.

Through Claudina’s story and those of other women who have suffered at the hands of strangers, intimate partners, and the security forces, Textures of Terror offers a deeper understanding of the complexities of seeking justice in post-conflict countries.

This book is a must-read for anyone interested in human rights, violence against women, and the struggles those seeking justice in Guatemala face.

In the following interview with Barriozona Magazine, Sanford discusses the factors that contribute to the dangerous environment for women in Guatemala and why she chose the case of Claudina Isabel Velásquez’s murder as a focal point for her investigation.

What do you hope readers will take away from your newest book, Textures of Terror: The Murder of Claudina Isabel Velásquez and Her Father’s Quest for Justice?

My intention is that the women’s stories in Textures of Terror will help readers understand the violence and corruption that is driving women and children to flee Guatemala. Women are compelled to flee with their children when they encounter violence at every turn, when there is no justice, and when the very officials charged with protecting them are the ones violating their rights.

Violence against women and feminicide in Guatemala is a serious and widespread problem. What was the deciding factor in choosing, among others, this young woman’s murder case?

Guatemalan human rights leader Amilcar Mendez asked me to meet and accompany Claudina Isabel’s father, Jorge Velásquez, as he sought justice for his daughter’s murder. Claudina Isabel had been in her first year of law school with Amilcar’s daughter. I had previously accompanied Maya massacre survivors seeking justice, so I mistakenly assumed Jorge was Maya. To my surprise, he was a tall, white, conservative, evangelical, upper-middle-class auditor from Guatemala City. I initially did not understand why he needed accompaniment. Until then, I had never considered that justice was as inaccessible for people like Jorge as it was for my Maya friends.

In many ways, human rights research is serendipitous. I did not really choose this case; it chose me. Jorge is relentless in his quest for justice. I accompanied him as he basically did an audit of the legal system and its response to the murder of Claudina Isabel. What happens when a woman is murdered in Guatemala? What are the crime scene protocols? The forensic autopsy practices? How do police investigate the murder of a young woman? How do prosecutors build a case? As we found huge gaps in each phase of the investigation, we began to ask what should happen? What are the international protocols? Why aren’t they followed, and who benefits from impunity? Jorge’s encounters with police and prosecutors offer an up-close appraisal of the inner workings of the Guatemalan criminal justice system and its maintenance of inequality, patriarchy, power, and impunity. Jorge’s story puts a human face on the fallout of structural state violence.

The book’s title contains a dreadful word: terror. Does this term correctly describe the social environment Guatemalan women live in?

Yes, absolutely. Terror is the correct word to describe what it means to be a woman confronting impunity while living on the uncertain and hazy frontiers of life and death in Guatemala. My book is about the private traumas of women as they face terror as well as their own feelings of inadequacy in the midst of unimaginable levels of violence. Prosecutors and police presume that certain kinds of women, such as prostitutes, do not deserve protection and have no rights. And so, when they encounter a crime against a woman, that attitude combines with a “blame the victim” mentality, allowing them to dismiss the victim as someone whose death does not merit investigation. The slightest details, like Claudina Isabel’s sandals and navel ring, lead them to conclude that she was a prostitute. And even when they are proved wrong, they still insist that sexual freedom must be the cause of this promising law student’s death by claiming that the victim “went to meet a boyfriend” or had “snuck out to meet a man.” They treat women as responsible for their own murders.

What underlying factors create this dangerous environment for women in Guatemala?

Guatemala suffered a genocide perpetrated by successive military regimes from 1978-1983. This genocide was part of a violent counterinsurgency war begun by a U.S.-backed coup in 1954 and carried out by the Guatemalan military against the civilian population. All told, more than 200,000 people were killed, 50,000 people were disappeared, 626 villages were massacred, and 1.5 million people were displaced. Despite peace accords in 1996, followed by a truth commission in 1999, and uneven but ongoing prosecutions of perpetrators, the structures of violence that facilitated these repressive regimes have changed little. A UN Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala found that in 2015-2016 only 43 percent of gender violence cases were even accepted by the prosecutor’s office – meaning that 57 percent of the cases never even made it to the investigator’s docket. There is a 98 percent impunity rate for the murder of women, meaning that only two percent of cases are prosecuted and resolved.

A survey of male attitudes about violence against women found that 58 percent of Guatemalan men believe they have the right to use physical violence against their spouse. Repressive structures place women and their bodies on the frontlines of retaliation against their male relatives in the same way that patriarchal structures place women under the “protection” and “discipline” of their male relatives. In the end, this violence against women and the murder of women today is a driver of migration, and it is tied to state inaction and impunity.

For families of feminicide victims, losing a loved one is often the first link in a long chain of adversities, particularly for parents who want justice for their daughters. How did you incorporate this aspect into Textures of Terror?

The long chain of adversities for families seeking justice is absolutely heart-wrenching. In the end, the book is part memoir because Jorge and I worked together on his daughter’s case for more than a decade. So, the book is about our shared experiences as well as his quest and how we both tried to make sense of the labyrinth. We went to police and prosecutor offices and the embassy and NGO offices in Guatemala. I organized speaking engagements for him in the U.S. and abroad. Amnesty International declared Claudina Isabel’s murder and the subsequent lack of justice to be an emblematic case of the Guatemalan feminicide. The adversities are more than government inaction. Most shocking to me was the official dismissal of the value of human life, the denigration of the victim and her family, the slandering of the character of the victim, the disparaging of the integrity of the victim and her family, and suggesting of ulterior motives because a father has the temerity to want justice for his daughter’s murder. Ultimately, we went to the Inter-American Court with Claudina Isabel’s case. Surviving all this and continuing to seek justice, one realizes that justice can only ever be bittersweet because nothing will bring back Claudina Isabel.

As Guatemalan citizens leave their country by the thousands, women are still vulnerable to the same kind of violence they face in their native land as they try to reach and cross the U.S.-Mexico border. What does this tell us about violence against women in a larger context?

Women are vulnerable to gender violence everywhere in the world. In her opening statement before the Inter-American Court, Jorge’s co-counsel Kerry Kennedy, president of the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Human Rights, said: “Violence against women is the greatest challenge presented to the international community today…. Across the globe, women who are badgered, beaten, brutalized, mutilated, and raped can expect police, judges, and prosecutors to humiliate victims, fail to investigate cases, and dismiss charges. Worldwide, at least one of every three women – more than two billion women – will be beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused in her lifetime. Women constitute half the world’s population, perform nearly two-thirds of its work hours, receive one-tenth of the world’s income, and own one-tenth of the world’s property.” Inequality is the larger context of violence against women everywhere.

How do you see the issue of violence against women in Guatemala fitting into the larger global conversation about gender-based violence and human rights?

The 1999 Commission for Historical Clarification report confirms that the state trained its soldiers and other armed agents to rape and terrorize women. During the war, army soldiers and other security officers were responsible for 94.3 percent of all sexual violence against women. Today’s violence against women in Guatemala tells us a lot about what it means to grow up in ambient terror and its aftermath.

Women’s rights are human rights. In the past, the tendency was to look at state responsibility for human rights violations when the state directly committed the violation with intent. Gender discrimination in Guatemala further reinforces the very tenets of state responsibility for feminicide in Guatemala, whether by state commission of the crime, toleration of the crime, or omission of state responsibility to investigate and sanction violence against women. Impunity rates for violence against women are markers to measure the efficacy of state policies. A 98 percent impunity rate for the murder of women protects perpetrators, not victims.

What are the most urgent measures to effectively address violence against women in Guatemala?

Corruption and impunity form the vortex of violence against women in Guatemala. Guatemala urgently needs a functioning justice system. Unfortunately, contemporary corruption and threats of violence have driven more than 30 Guatemalan anti-corruption justice operators (including attorneys general, judges, and prosecutors) to seek exile in Mexico, Spain, and the United States. Whether justice operators seeking to prosecute corruption or regular citizens trying to take a bus to work without having to pay a “tax” to the local gang, the rule of law is essential for Guatemalan society to give its citizens a measure of security. Corruption drives legal and illegal migration because it collapses public space and civic possibility. Migration from Guatemala went down 35 percent during the UN International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala‘s (CICIG for its acronym in Spanish) first year of anti-corruption work in Guatemala. For five years, the number of Guatemalans apprehended at the U.S. border continued to drop. CICIG’s successes are a model for the region to follow to fight against corruption and slow the exodus of citizens.

While disliked by the powerful and the corrupt, CICIG had a 70 percent approval rating in Guatemala in 2017. Working with Guatemalan prosecutors, CICIG dismantled more than 70 criminal networks, investigated, and prosecuted 100 high-impact cases, brought 600 suspects to trial, and convicted 400. CICIG prosecutions supported Guatemalan prosecutors and made it possible for regular citizens to access justice. As the powerful and corrupt ramped up unrelenting attacks on CICIG and the Trump administration was silent, then-President Jimmy Morales, who was himself under investigation and had an approval rating below 20 percent, did not renew CICIG’s mandate in 2019, and a record 264,168 Guatemalans were caught on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Are grassroots efforts in Guatemala helping to change this problem?

There are many grassroots efforts from local groups to regional groups seeking to support victims and push for justice. Unfortunately, the current regime in Guatemala is criminalizing prosecutors and judges who challenge corruption or simply attempt to do their jobs with transparency. When judges and prosecutors cannot safely carry out the work of justice in their official positions, local community leaders are at greatest risk. I was recently speaking to a human rights lawyer in Guatemala who told me that he sees the criminalization of women lawyers as the latest nodal point of attack on rights in the ongoing efforts of the oligarchy and organized crime to maintain power through impunity.

What one point can your book make to fulfill your intended purpose in writing it?

That one person can make a difference even in the face of structural inequality and violence. That a grieving father turned his anguish into an international campaign for justice for women in Guatemala and honored his daughter’s memory by never giving up the struggle for justice. That citizens can hold their governments accountable.

| Victoria Sanford is a John Simon Guggenheim Fellow and Professor of Anthropology, City University of New York. She has given expert testimony on the Guatemalan genocide in international courts and authored seven books, including Buried Secrets: Truth and Human Rights in Guatemala. Web: www.victoriasanford.info |

© 2023 - 2024, Eduardo Barraza. All rights reserved.