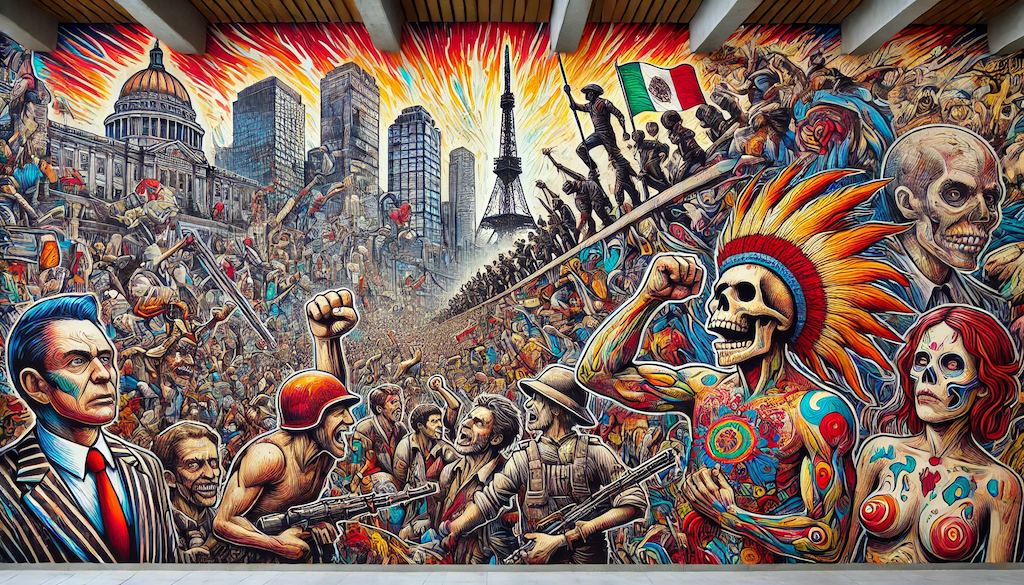

More than a century ago, Mexican artists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros turned muralism into a political weapon, while José Guadalupe Posada did the same with the art of engraving.

Through murals and engravings, they shaped collective consciousness, educated, provoked, and unified a post-revolutionary Mexico. Their work was not just an aesthetic expression but a strategy of intervention in public space, where art functioned as a means of mass communication.

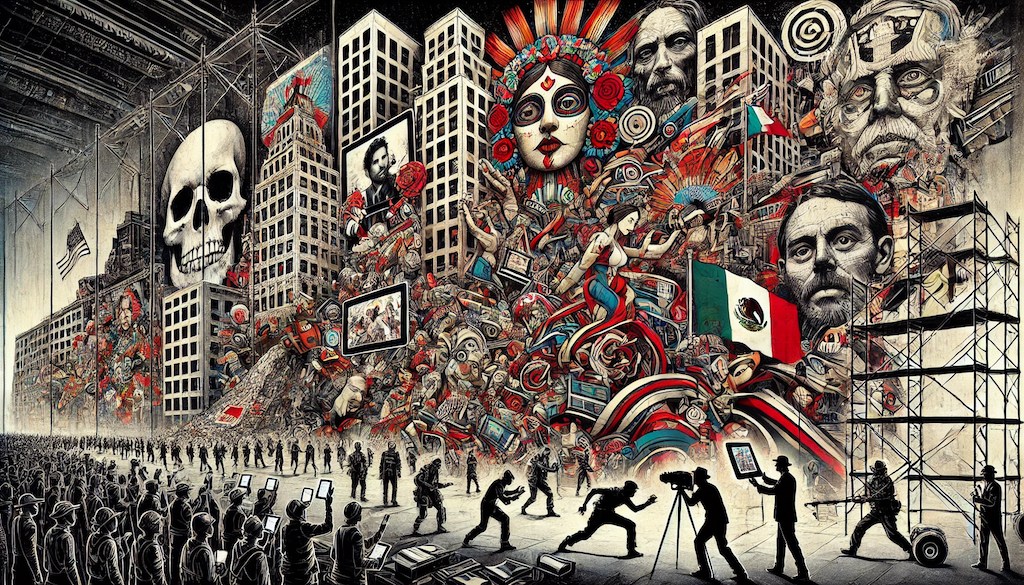

But in an era where activism spreads through viral social media posts, AI-generated art, and immersive installations, how does their legacy translate today? If muralism was once the people’s loudspeaker, is it still relevant today, or has social criticism evolved into completely different forms?

Posada’s calaveras: the first political memes

José Guadalupe Posada, the engraver behind Mexico’s most iconic calaveras, never saw his work displayed on government walls like Rivera and other muralists. His illustrations circulated widely in newspapers and pamphlets, denouncing political corruption and inequality with dark humor that made criticism digestible. His skeletons were not merely festive figures; they were visual allegories that dismantled power and exposed its fragility.

A century later, his approach feels eerily modern—his engravings functioned much like today’s political memes, using satire and exaggeration to challenge authority.

If Posada were alive today, would he still rely on traditional printmaking, or would he animate satirical reels on Instagram? Would his calaveras take the form of AI-generated deepfakes exposing political hypocrisy? Would he harness the viral nature of social media to reach the same massive audience he once achieved with paper and ink? His legacy reminds us that political art does not need a wall—it needs an audience. And today, that audience consumes content in fleeting bursts, mediated by algorithms, rather than through static images.

Rivera’s grand narratives in a fragmented era

Diego Rivera painted monumental, state-funded frescoes that depicted Mexico’s history as a linear, heroic struggle. His murals narrated the Revolution, industrialization, and indigenous heritage as a singular, unquestionable story. In his time, these works were not only artistic expressions but also instruments of national identity construction.

But in today’s media landscape, where TikTok and other platforms rewrite history in real-time, do monolithic narratives still resonate? Trust in singular narratives has eroded, giving way to a more decentralized discourse where multiple voices challenge official versions.

Rivera’s murals were effective when the state controlled information, but today, the public distrusts hegemonic narratives and demands more inclusive and decolonial histories. If Rivera were working today, he might find himself embroiled in debates over his idealized portrayals of laborers or his paternalistic perspective on indigenous communities. Would he abandon frescoes in favor of augmented reality murals that shift depending on the viewer’s identity? Would he still paint walls, or would he design interactive digital installations that respond to real-time social movements?

Orozco and uncomfortable truths in the age of algorithms

José Clemente Orozco rejected both state propaganda and the idealization of the Revolution. Unlike Rivera, his work did not celebrate victories—it warned against fanaticism, violence, and the betrayals of power. His murals were a harsh mirror of history, unsettling and demanding reflection.

Today, as ideological discourse radicalizes within algorithm-driven echo chambers, Orozco’s stark vision remains necessary. If he were alive today, how would he depict a world where social media amplifies outrage while often erasing the complexity of debate? Would he denounce digital radicalization? Would he transform his war scenes into virtual reality installations confronting audiences with the brutality of modern conflict?

Or, on the contrary, would he struggle to connect with an audience that prefers curated and filtered content over the challenge of raw and uncomfortable truths? In an era where information consumption leans toward escapism and bias confirmation, would his uncompromising vision still hold its impact?

Siqueiros’ experimental fire vs. AI’s algorithmic precision

David Alfaro Siqueiros was the most radical in both technique and ideology. He used spray guns before the rise of graffiti, incorporated industrial materials, and championed art made by and for the people. His murals were dynamic, aggressive, designed to engulf the viewer in revolutionary fervor.

But today, the relationship between art and control over discourse has changed. Artistic authorship is no longer in the hands of the individual but is constantly challenged by the rise of collective digital art and artificial intelligence. AI-generated art, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and decentralized platforms have reconfigured the notion of artistic ownership.

Would Siqueiros embrace AI as a democratizing tool, or would he see it as a capitalist product that dehumanizes art? Would his digital murals generate images that shift in real-time based on social movements and state surveillance? His experimental spirit suggests he would not fear new media, but can digital platforms replace the physical, immersive power of his monumental works?

Is muralism still a catalyst for social change?

Public art remains relevant, but today’s walls are not just concrete—they are digital, ephemeral, and interactive. Muralism continues to be a symbol of resistance, as seen in urban interventions by the Black Lives Matter movement or feminist street art across Latin America. However, today’s most effective political imagery spreads through screens, evolving at the speed of information flow.

If Posada, Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros were artists today, they would be navigating a world where visual protest occurs as much in pixels as in pigment. Would they opt for virtual reality graffiti, hack corporate digital billboards, or use AI to generate viral content against authoritarianism?

Muralism was never just about aesthetics—it was a means of mass communication. And while the tools have changed, the need to challenge power through imagery remains intact. The question is not whether muralism is still relevant, but whether today’s artists can adapt its essence to a world where walls are no longer the only canvas.

EXTERNAL LINK → 100 Years of Muralism in Mexico

© 2025, Eduardo Barraza. All rights reserved.